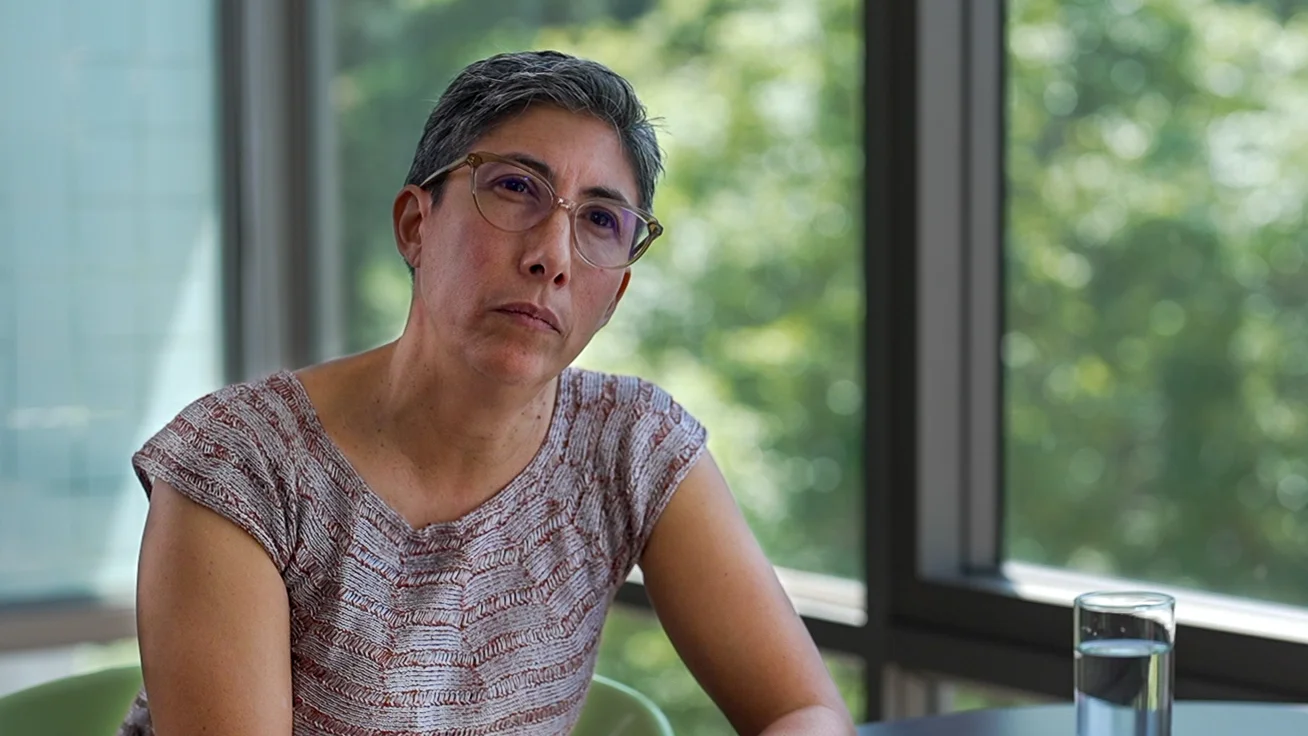

Marcela Eslava Mejía

PhD in Economics from the University of Maryland at College Park, and economist from the University of the Andes. She is a tenured professor and was Dean of Economics at the University of the Andes. She has been elected president of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association (LACEA), and is a member of the Board of Directors of the Research Institute for Development, Growth and Economics (RIDGE).

Interview

Q/ In addition to having low per capita income, the region shows high levels of inequality in income distribution. Part of your research identifies some structural reasons behind this inequality, which is also associated with productivity tests, in particular, the distribution of firms, labor market segmentation and market power. Can you elaborate on these findings and what implications they have for policies that seek to reduce inequality? What synergies do you see between productive development and inclusion?

Latin America combines low levels of per capita income with very high inequality. One peculiarity of inequality in Latin America is that it is very much driven by poverty, by having many people with low income, and not just by having some people with a high level of income. These two problems are not unconnected; they are manifestations of the same basic characteristics that Latin America has. Ultimately, it means that we have a very large mass of the population that is unable to engage in the most productive activities, that is, in activities where they could generate the most income for themselves and their families, and where, at the same time, they could contribute the most to the economy.

These are manifestations of some fundamental factors, of which there are many, but I would say two are very prevalent. One is that people have a human capital formation that is, on average, low, but also very poorly distributed. Again, there is a large mass of people who in the end have not been endowed with sufficiently significant productive capabilities. But, at the same time, we have a design of the regulatory apparatus and of the social protection apparatus -a design of the rules that govern both the way in which people enter the labor market and the way in which the productive apparatus is organized- that are incompatible with these basic capabilities that we have.

The productivity of people are regulations that are burdensome to generate productive activity. For example, the high costs for a person to be linked to formal employment. In some countries, this has to do with minimum wages that are above the productive capacities of many people. In other countries, it has to do with other costs of formally linking a person. And this disconnection between people’s productive capacities and the rules with which they should be linked in order to be really involved in high productivity activities, end up generating this situation that we have. Of course, those rules are not capricious. They are there precisely to protect people. The minimum wage is there to ensure that people do not have too low an income.

Certain additional costs, for example, that the employer has to contribute to the person’s pension, to pension savings, are also there to eventually protect people. However, there is a disconnect. They are designed in a way that makes them unviable for the income-generating capacities of many people and, in general, of countries. In the end, it is this disconnection that is a fundamental element that we have to solve and that brings with it many other manifestations.

We have a lot of very small companies, in fact, an enormous predominance of one-person companies, what we know as «cuentapropismo» (self-employment). Moreover, this is also manifested in a low level of innovation. Since there is no apparatus to organize more powerful productive units or to provide sufficient incentives to do so, then, there are also few incentives for innovation, for investing in trying to have larger productive units. So, in the end, all these factors combine to generate the development problem we started with: low per capita income and high inequality.

Q/ In the region, the business structure differs significantly from the structure of developed economies, with a high proportion of employment and other productive factors concentrated in small, informal and low-productivity companies. How does this business composition contribute to the region’s low aggregate productivity?

Latin America is characterized by a peculiar productive apparatus when compared to that of high-income countries. Perhaps the most striking manifestation of this peculiarity is the enormous predominance of very, very small productive units. Many of these are self-employed, one-person productive units, but also very many micro-enterprises. To get an idea of how prevalent that is in Latin America, one could talk about the numbers of where people are employed in Latin America. About 70 % of the employed people in Latin America are self-employed or working in microenterprises, and only the rest are working in small, medium and large enterprises, in particular, of ten or more workers.

This contrasts sharply with what happens in high-income countries. In those countries, the proportion is exactly the opposite: 70 %, and in many of them 80 % or even more, of the people effectively linked to productive activity are in units of ten or more workers. This contrast is, in turn, a very strong manifestation of the productivity problem, because what it means is that we organize the productive activity, the one that generates income for all people, the one that generates added value for the economy, in a very, very weak way.

In the end, these forms of organization generate a very large productivity gap with those countries that are more developed. It is not that they are the cause of low productivity, the way we organize ourselves, or they are not exclusively the cause. In the end, they are also a manifestation of the problem of having a social organization with people who in many cases have low productive capacities to begin with. But it ends up being exacerbated when these people, in addition, are organized in forms of production that are not modern, that are not complex and that, for the same reason, have a low capacity to generate added value. And, therefore, this, in the end, means low productivity. That is, low value added for each person who participates in the productive activity, for each resource that he/she brings, for each unit of resources that he/she brings to the productive activity.

This is also highly correlated with the high informality that we see in Latin America . High informality is the fact that many people are linked to productive activity, but without being covered by all the elements of protection that one would expect them to have there, i.e. labor protection, for example. People who are in informality, either working on their own account or in companies that do not comply with labor rules, are not enjoying the labor protection that the rules are intended to provide. Informality is also the operation of a company that in itself, for example, does not pay taxes, does not report to the authorities and so on. And again this is a manifestation of the problem of low productivity, of the low capacity of the average human talent we have, but at the same time it also ends up contributing to worsen the problem of low productivity.

Q/ What are the main factors that explain the poor allocation of resources and the high level of informality in the region? What public policies are appropriate to favor productivity in a context of small and informal companies?

One dimension of the problem of low productivity in Latin America, of course, has to do with the fact that different companies have, on average, lower productivity than those in more developed countries. This is true, not only for companies, but also for any productive unit, including self-employed people. But there is also an additional factor that is sometimes hard to imagine. It is the fact that the most productive companies, which are those with the greatest capacity to absorb more people as labor force, to pay them better wages – precisely because they create more productivity -, which generate more added value for each person they hire and, therefore, could pay them more, which could generate greater welfare in this way, do not grow as much as they should. In other words, they do not end up absorbing as many people as they should. Meanwhile, the companies with lower productivity, the productive units that have less capacity to generate good income, become larger than they could ideally be. Sometimes they survive longer than they ideally should.

When I say ideally, what I mean is that if a company or a productive unit of very low productivity, of very low income capacity, were to close and that person who suddenly works, even on his own account in that business, were to move to one where there are other people, but which has more income generating capacity per head, he would surely improve his income and what he contributes productively to the economy. We call this the problem of misallocation of resources, the problem that we have many people «trapped» in productive units with low income generating capacity for themselves and for the economy. So, one of the big questions we ask ourselves is why, why do we have this problem of misallocation of resources?

When we ask ourselves that question, we go back to one of the factors I was mentioning before, which is the misalignment between many of the regulations we have in the economies and the productive capacities we have. So, for example, when a while ago we were talking about the problems of having a minimum wage misaligned with the productive capacities of the people, which is much higher than the productive capacities, the income generation capacity of many people, what that in the end means is that a person who, for example, working on his own account, makes an income, if we were talking about Colombia, of COP 800.000, which is a fairly prevalent income among people in Colombia, but would have to earn a minimum wage of COP 1,300,000, plus some additional costs for the employer. So, let’s say that the employer would end up paying COP 2 million per month for that person, but the person on his own only generates COP 800,000, which is a manifestation of his income generation capacity.

So, a person who has the capacity to contribute to the generation of income of COP 800,000, someone who hires him/her, and that person generates a level of additional income for the company more or less in that range, would have to be paid well above that income generation. And that, in many cases, is not even possible for a company because they would be hiring someone who brings them less revenue than they would have to pay. There are many, many examples of this type of misalignment of regulations in tax elements, in elements such as the minimum wage. Those that, in the end, end up dividing the economy between an informal sector that does not pay all those costs and a formal sector that does have to be tied to them, end up generating a very important piece of the misallocation of resources, which is the piece of having too many people and too many factors and productive capacities trapped in businesses that are off the radar of those regulations, which in the end end end up being informal in their great majority, very small and very little generating high income.

Now, within the formal apparatus and the slightly larger companies, including small and medium-sized companies, but not micro companies, with lower productivity, in that segment we also have problems of resource allocation, many of them associated with rules and elements of the productive environment that make it more costly to become larger, such as tax codes that say that if you exceed a certain size, you will have higher taxes. This, obviously, becomes a disincentive to grow, for example, above that size, and then it ends up generating, on the one hand, disincentives to grow, but at the same time a bad allocation of resources, because that company that is more productive, that could grow more and therefore absorb more workers who would benefit from that higher income, does not do so. These combinations end up generating a misallocation of resources and add to the basic problem of low productivity of having productive input capacities that are far from the global production capacity frontier.

Q/ It is often argued that low productivity is also associated with the growth dynamics of companies throughout their life cycle. What role does this phenomenon play in explaining the region’s low productivity? What is this dynamic in the region and how does it contrast with the developed world? What are the drivers of company dynamics in the region?

One of the characteristics of the productive apparatus in Latin America is that companies grow, on average, less than those in economies that we would like to resemble in terms of per capita income, those that are richer and where people have higher incomes. And that is not only, or does not necessarily mean, that all companies grow less, but it has the peculiarity that especially those that could be more dynamic, that could become those superstars, grow less than they do in more developed countries.

The 90th percentile, so to speak, grows at a slower rate, while, on the contrary, the lower productivity firms, which one would expect in a healthy economy not to grow as much, or even to exit the market and hand over those productive resources to other higher productivity units, grow more than they do in those economies. In the end, the average is a more muted growth, which ends up being in turn a manifestation, but also a cause, of the misallocation problem. In what sense is it a cause? Precisely because the companies that are more productive and that could generate more income for people, grow less than they should, and then end up being less large and absorbing fewer people, which is precisely what we defined earlier as the misallocation problem. But it is not only a cause, it is also a manifestation of the very factors that ultimately generate that misallocation. For example, if we were talking earlier about underlying factors that make it very costly to have a large company because it is taxed more or because it ends up subject to regulations that other companies would not have, then, as this becomes a disincentive to grow -and it is precisely the most productive companies that would most like to grow-, these same factors end up being the same factors that ultimately generate the misallocation, in the end, these same factors that discourage growth also end up being an explanation of why we have less business growth than we would like and, therefore, less growth in people’s income and modern jobs, which in the end are a welfare problem for people in Latin America, particularly in their link to the labor market.

Q/ How important are differences in innovation in explaining the productivity gap between Latin America and the Caribbean and developed regions? What are the most effective policies for promoting research and development and fostering technological adoption in the countries of the region?

A very important element of productivity growth, of the productive capacities of companies already organized as such, is innovation. And this, on the one hand, in the sense of adopting better production techniques, but also, and above all, in the sense of inventing better products and services that are more desirable for people, but that also generate more added value for the company, for the economy and for the people who are linked to that company. Unfortunately, Latin America is also lagging behind on this front. There is much less innovation: we invest less as a country, both privately and publicly, as countries, in these innovations than would be desirable in order to achieve better growth and welfare. This, on the one hand, results precisely from not having sufficient incentives for growth, but rather disincentives to higher productivity activities. But, at the same time, it can be encouraged not only by eliminating the distortions we were talking about earlier, but also by direct interventions to improve these innovation capabilities. And in these there are, for example, management and entrepreneurial training programs. When I say entrepreneurial, I am talking about transformational ventures, about what can really be a powerful company, in the sense of being able to absorb many people and generate a lot of added value to the economy and to the people.

Therefore, generating, for example, entrepreneurial education programs that bring entrepreneurs together with their potential clients, that teach them where their greatest needs and desires are, and what the standards are in the world, becomes an important element. It is known that Latin America has very important gaps in managerial capabilities. In the same way, we know that there is a big gap in interventions that help to develop better management capabilities, that is, capabilities to organize production processes, administrative processes, human resource monitoring processes in accordance with international standards, and we know that Latin America has a big gap there. And we are aware of programs that are functional to improve these capabilities. Therefore, there are also some very important elements for intervention. But innovation is also an element where there is a lot of room for investment of public resources, both in the generation of public goods necessary for innovation, such as better certification capabilities, for example, of quality standards, such as laboratories for testing new techniques, and not only in these public goods, but also in the direct public investment of resources for innovation in sectors where the need for large scale is sometimes more compatible with the investment of public resources or with the complementation of these with private resources. In all these areas there are very important areas of work for Latin America.

Q/ The creation and destruction of companies is also a relevant phenomenon for aggregate productivity. How does this «selection» phenomenon work in the region compared to its dynamics in the developed world? What role does this process play for productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean?

Earlier we were talking about the low growth of existing companies in Latin America, but there is also, in addition to this characteristic of the dynamics of those that are already here and that remain, an associated dynamic of new companies entering and existing ones leaving, but which are not able to generate sufficient income for the company, for the workers associated with it. And that is a dynamic that in a healthy economy and, in general, in high-income economies, is very busy. There is a lot of entry and exit and we know that this contributes in a very important way to productivity, because new ideas come in, new products come in with these new companies and many of them have the potential to grow. Some of them will discover that they didn’t really have a powerful market and they will end up staying small or even going out of the market.

Latin America has a muted dynamic of entry and exit of companies. The two things are always linked: When there are more outflows, new spaces open up in the markets and, therefore, this leads to more inflows. Then, when the outflow is off, there is also less inflow. And, indeed, the numbers, which are also somewhat difficult to construct adequately for Latin America because the data is not sufficiently comprehensive of the new productive units and of the different sectors, but the data that we do manage to have shows off numbers, both of entry to new companies and of exit and, in particular, as we mentioned before, of exit of the less productive companies. On the one hand, this is associated with exactly the same factors we mentioned before. These factors that discourage business growth also discourage entry, because if growth is not sufficient because the owners of these productive units do not see enough profit in it, those who are thinking of creating a new productive unit do not see enough promise of income generation in many cases either, and this partly explains why we have low entry of companies. So, these factors are still underlying and are the same ones that contribute to the low inflow and outflow.

Likewise, we have to distinguish market entry from entry into formality. Many of the figures we have for Latin America are measured from the companies’ records with the government and, therefore, in reality, what they are measuring is the entry into formality or formal production, and when they disappear from those records, they measure the exit from formal production. Many of these companies that leave may indeed leave the market, some of them may be becoming informalized, and vice versa, some companies that enter the formal registries may already have existed previously but may not have been registered. Thus, given that there is a dimension of entry that has to do with starting to exist in formality, all the elements that make formality costly and discourage it also discourage entry into formality, and therefore play a very important role in this dynamic. I would say that beyond the elements we have already mentioned, which, in general, make business growth, the entry of new companies and so on, costly.

There is also a very peculiar element of Latin America. Latin America, on the one hand, already has an enormous prevalence of entrepreneurship. When we said before that there is a lot of self-employment, a large number of very «small» companies, this is also a manifestation that we have a lot of entrepreneurs, but compared to those countries with higher income, they are entrepreneurs who, in a very large mass, are in businesses that generate little income. In many cases, in fact, the businesses that we would call survival businesses, which barely generate enough income for the person or his family to have a minimum of survival but do not really generate an important welfare, nor an important level of income to the economy. This, to a large extent, derives from the combination of factors that we have already been discussing, but it also reflects a certain appreciation of this productive activity on one’s own account. Part of this may be cultural, but we have also been encouraging it even from the public policy point of view.

In Colombia, for example, schools have to teach entrepreneurship, but not at the same time the advantages of employability. Therefore, there is room for us to think about how, even from a public policy perspective, we can promote not only entrepreneurship, but also employability, and that would be a very important element to build a more dynamic entry of more powerful productive units.

Q/ It is argued that international trade is a strong ally for productivity. Through what channels can trade and the internationalization of companies improve the economy’s productivity? How can we promote the international insertion of the region’s companies?

International trade is an important ally of improved productive capacity, and it is so through at least two channels which, moreover, the literature has shown to be manifested in Latin America and has shown this from the different episodes of trade liberalization. A first element is competitive pressure. We complain a lot in Latin America that, for example, during the liberalization of the 1990s, many companies were unable to face foreign competition, and this is true. That, in itself, has a positive side, which means that many companies were subjected to having to compete with others, some discovered that they did not have those capabilities, and others developed them. And what we see in the research that has been done in Latin America is that, effectively, many companies with low productivity left, but others, which had better capabilities or were able to invest in improving them, raised their productivity standards. In the end, how is this reflected in people’s well-being? In many ways. For the employees of those companies themselves, what we have seen in the evidence is that there then began to be a greater demand for workers with higher skill levels, which in turn generated incentives and benefits for people in Latin America to become more skilled. And we see a long-term transition towards higher levels of qualification and income for those who managed to get into that package. There are benefits that go from the company becoming more productive to people being able to have better jobs in many of these companies.

At the same time, there is a benefit for consumers: Those of us who lived before the nineties and after, began to see a change in the type of consumption that people had, a greater equity in access to certain goods that were traditionally imported, either because they began to be produced internally thanks to that competitive pressure, or because they could be brought in from abroad. So, in that sense, there is a benefit from the competitive pressure channel. This does not mean that there are no costs. Many will be thinking, «yes, but, then, the low-skilled people found it more difficult to connect, they had a bigger income gap, because only the high-skilled people started to earn more». And it’s true, we see it in the evidence. What this means is that we have to understand how to take advantage of these benefits of international trade, which we see, which Latin America has somehow taken advantage of, but which also bring with them losses for some population groups. And this requires us to find a way to combine greater access to global markets with better capabilities for people, so that they can take advantage of the benefits of being in this globalized world. This means education and transformation of the productive capacities of those who are unable to enter this package.

In addition to competitive pressure, another very important channel, which was very beneficial to start linking us more to global markets, has to do with access not only to imported goods that people may want to consume, but also to inputs that were not possible before, or we could do so but at more expensive levels or with lower quality, and now we discover that they are produced elsewhere in the world with higher quality, which becomes an important input to produce higher quality goods.

In other words, there is also a channel that runs along the production chain, which means that the benefits of international trade are exacerbated and grow as we build on the production chain. This is a very important element that speaks of the importance of having access to better inputs. And that not only translates into me importing better or cheaper inputs, but also into competitive pressure on input levels. And it also leads to an improvement in the local production of those inputs. All these channels combine and speak of enormous gains that have brought and may in the future bring greater insertion into global markets. Particularly because Latin America is not very deeply inserted in global markets, despite the transformations it has undergone since the early 1990s. But, as I was saying, it has also taught us a lot about how these policies have to be accompanied by transition assistance. Because, although trade has positive net gains, it also has gains that are positive for some people, but negative for others. And even if the average is positive, the fact that it generates greater inequality is a concern that needs to be addressed when thinking about international trade.

The other very important element of international trade, which has to do with inputs, is the ever deeper development of global value chains: The fact that I can produce an input here that someone else will use, or a piece of a good that someone else will assemble or complement elsewhere so that it can finally be built in a third geography of the world is a potential channel for growth, which has been expanding exponentially in the world, and in which Latin America still has much room to insert itself and take better advantage of these gains.

To be able to do so, one needs a business environment that facilitates this insertion and that is flexible in order to adapt to the productive characteristics of a good that is made throughout the world.