Policies for adult life

Labor market insertion and asset accumulation play a determining role in the well-being of individuals and their families during adulthood. However, the persistence of structural barriers, such as labor informality, difficulties in accessing credit, gender inequality, ethnic-racial discrimination and regional disparities, restrict opportunities for quality employment and access to social protection mechanisms. When adding inequalities in human capital formation, the impact of all these barriers on labor income—the main source of income for Latin Americans and Caribbeans—is significant1. While income support policies for targeted groups are important to alleviate poverty, they are insufficient to address the deeper issues that sustain exclusion. This section focuses on addressing these structural problems by proposing policies that seek more equitable labor inclusion and expanded access to economic opportunities.

Families in poverty, particularly those in extreme poverty, need to be helped by the State, not only by offering them protection against risks, but also with some kind of income transfers. And here the region was a pioneer with the design of income transfer programs, but this is only one part of social protection.

Based on an interview with Santiago Levy

Increasing access to quality jobs for vulnerable groups

Limited access to formal employment, as documented in the previous chapters of this report, is one of the structural problems that condition social inclusion. Informal employment is characterized by low wages, high instability, low productivity and limited prospects for professional growth. The segmentation of the labor market also aggravates the gaps in access to social protection mechanisms, which in the region are mainly linked to formal employment (Álvarez et al., 2020). Given the challenges of labor markets, social connections, especially family connections, play an exceptional role as a mechanism for finding employment. But this dependence becomes, in the long run, an additional source of inequalities in access to employment opportunities: families of higher socioeconomic status have better recommendations and contacts than those of lower socioeconomic status (De la Mata et al., 2022).

As a general guideline, policies aimed at reducing the gaps in access to quality jobs for vulnerable groups should act on three margins: first, tending to equalize the productive potential of workers; thus reducing previously existing gaps generated by the history of human capital accumulation and by changes in labor market demands; second, making more equitable the way in which the labor market treats people with similar productive potential, but with distinctive characteristics such as gender or ethnicity; and third, helping disadvantaged groups to make more and better informed employment decisions.

Although differences in human capital are constituted at earlier stages, there are still opportunities for training during working life (Berniell et al., 2016). Education and job training policies-which include classroom training, on-the-job training through internships, or both-, have shown favorable effects in the region, especially for young people and women (Escudero et al., 2019). Despite the fact that developing countries used to hold a pessimistic view of these policies (McKenzie, 2017), recent research has demonstrated their effectiveness (Carranza and McKenzie, 2024). Successful examples include Jóvenes en Acción in Colombia (Attanasio et al., 2017; Ibarrarán et al., 2019), Programa Primer Paso in Argentina (Berniell and De la Mata, 2017), Projoven in Peru (Ñopo et al., 2007), and Yo Estudio y Trabajo in Uruguay (Le Barbanchon et al., 2023).

We must overcome the idea that all human capital formation takes place only in educational institutions. There is a lot of room for human capital formation in the companies […] And this dimension of human capital formation, in my opinion, has been highly underestimated.

We already have millions of workers in the region who are 30 years or older and who will be in the market for the next 30 years. We cannot waste this human capital, and there we have an important room for improvement.

Based on an interview with Santiago Levy

Moreover, in the face of changing labor demand, driven by technological transformations and the energy transition, it is crucial to readjust training policies to strengthen the skills of vulnerable workers. Technological advances may lead to the replacement of workers by machines or the digitization of routine tasks (both manual and simple cognitive) in certain jobs; they may also increase the productivity of some workers in non-routine tasks and expand job opportunities in new tasks (Álvarez et al., 2020). On the other hand, the energy transition is expected to have an impact on employment levels and on the profile of skills required (Álvarez et al., 2024). In this context, there should be public policies that monitor these changes and offer retraining to affected workers to ensure their transition to these new job opportunities.

According to data from the 2019 CAF Survey (CAF, 2020), almost half of the workers in Latin American cities are concentrated in occupations with a high content of routine tasks (47 %, on average, in the main cities of the region, compared to 41 % in the United States). Analysis by socio-demographic characteristics indicates that workers with lower educational levels, middle socioeconomic family backgrounds and young people may be the most affected by automation. Brambilla et al., (2023) document the effect of the incorporation of robots in the labor markets of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, the main users in Latin America. Robots mainly replace formal salaried jobs, affecting young and semi-skilled workers to a greater extent. This induces displaced workers to seek options in informal jobs to escape unemployment. Among those who do not lose their jobs, robotization generates greater wage losses for middle-aged and older formal workers.

Another active employment policy focuses on supporting workers in obtaining a job, reducing the asymmetry of information between them and companies, or reducing the costs associated with the search, which are particularly high for vulnerable groups. Among these policies are employment exchanges—which provide information on job vacancies to workers and about them to companies—support policies in the search process, including help on how to prepare a résumé, and training in interview skills. Also, the certification of competencies based on the evaluation of workers’ productive capacities, and the encouragement of the development and use of digital job search platforms. Another type of policies that can contribute to improving decision-making at key stages of working life are those that provide information on the quality of available jobs and the future potential of occupations. These types of interventions can be especially important for young people at the time they enter the labor market, as these first work experiences condition future trajectories (Berniell and De la Mata, 2017). Taken together, these policies can help broaden the spectrum of labor opportunities for the most vulnerable groups, and thus reduce dependence on their social ties.

In terms of these business services, the time zone matters more […] than how many kilometers away you are. And that makes it possible for Latin America to integrate north to south in terms of providing business services that could be using our growing university-educated population.

Based on an interview with Ricardo Hausmann

Reducing spatial inequality in job opportunities

Spatial inequalities are a crucial factor in the employment opportunities of vulnerable groups. Geographic location and access to transportation can significantly determine the possibilities of obtaining formal employment or improving working conditions. In Latin America and the Caribbean, productivity gaps between regions limit opportunities for those residing in less developed areas (Alves, 2021). Public policies can address these gaps through a territorial approach that reduces inequalities in access to basic services (education, health, infrastructure, etc.), thus strengthening their productive potential.

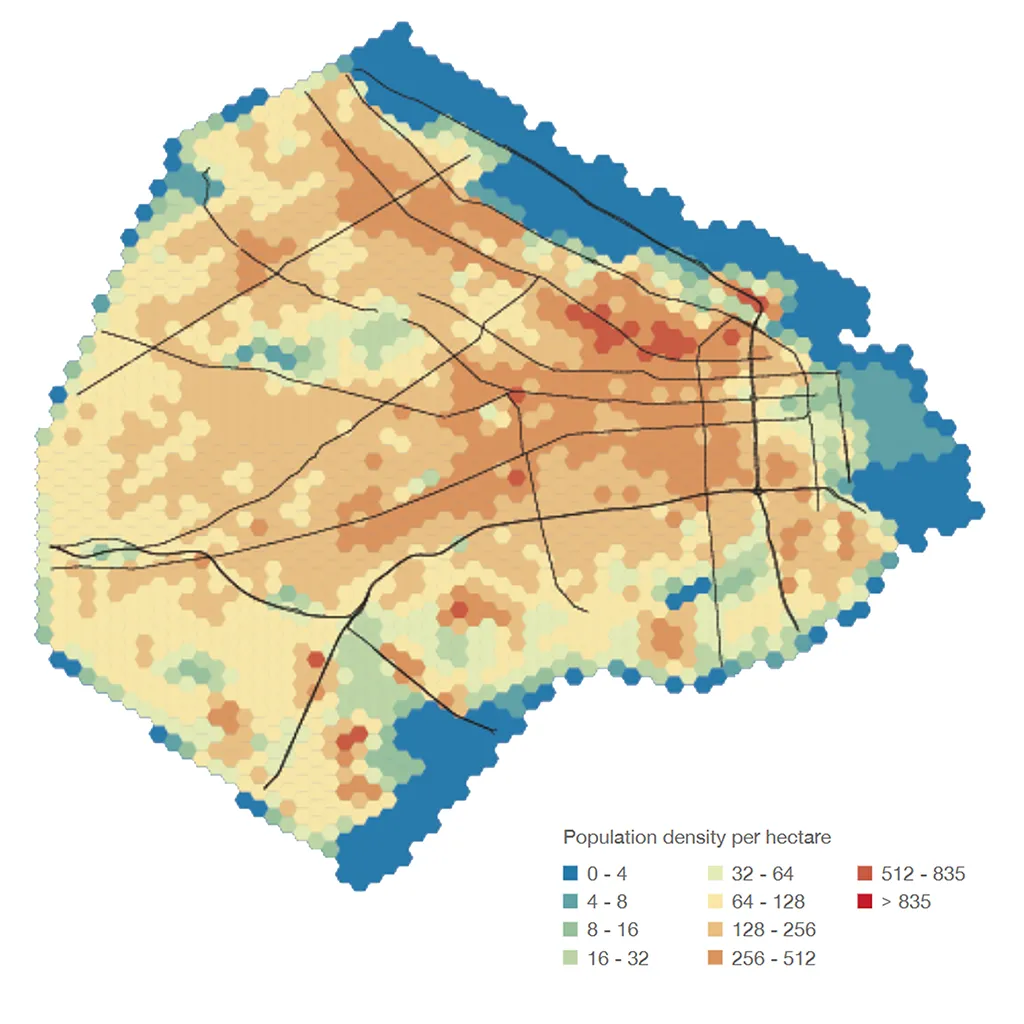

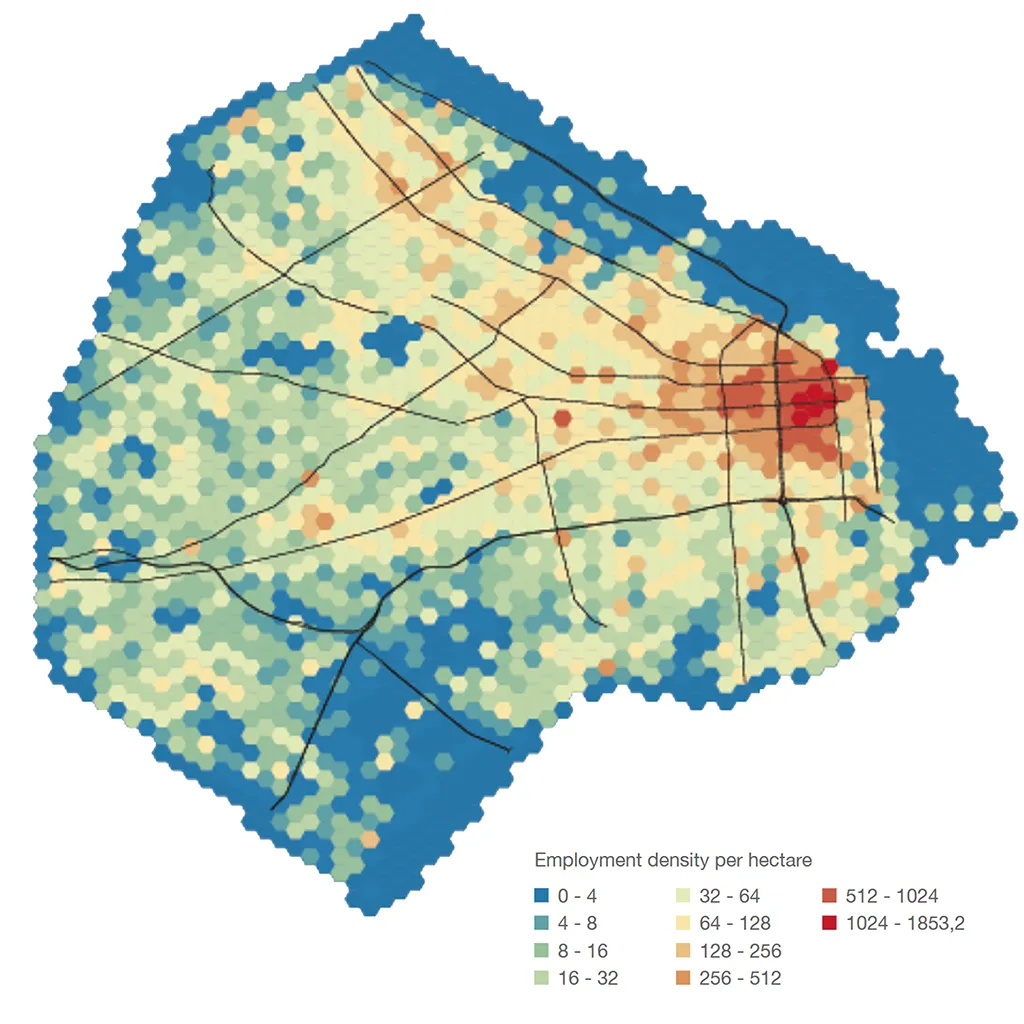

Within cities, spatial inequalities are also evident. Formal jobs tend to be concentrated in central areas, generating disparities in distances to the workplace. In the city of Buenos Aires, for example, half of the formal jobs are concentrated within a four-kilometer radius in the center, while the metropolitan area extends for tens of kilometers (Alves et al., 2018) (figure 3.10). Similar situations occur in São Paulo, where inhabitants of peripheral areas have access to less than 20 % of jobs that are less than an hour’s drive away, in contrast to more than 50 % for inhabitants of the center (Pereira et al., 2020). Compounding this inequality are the high transportation costs and high congestion that are characteristic of Latin American and Caribbean cities (Daude et al., 2017).

Figure 3.10 Population and private formal employment density in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, 2017

A. Population density (average persons per hectare).

B. Density of registered employment in the private sector (total average employment per hectare).

The active labor market policies previously described, especially those focused on helping workers get jobs, can be key to addressing the spatial barriers that cause workers to limit their job search in cramped environments within cities (Berniell et al., 2024; Manning and Petrongolo, 2017). However, because a significant part of the constraints originates from the commuting costs faced by the most vulnerable populations, the expansion of public transportation infrastructure should be thought of as an effective tool to bring job opportunities closer. A recent study on the expansion of the subway in Mexico City showed that improving access to the city center, where formal jobs are concentrated, reduced levels of informality in peripheral neighborhoods and increased the welfare of its inhabitants (Zárate, 2022).

Eradicating all types of ethnic-racial discrimination

The indigenous and Afro-descendant populations of Latin America and the Caribbean face systematic penalties in the region’s labor markets. These are reflected, among other things, in fewer opportunities for formal employment and, when they do obtain them, in lower incomes. Part of these ethnic-racial gaps can be explained by differences in human capital formation, as noted above. However, another significant part has its origin in discriminatory behavior in the labor market. So-called «statistical discrimination,» where employers base their decisions on observable traits like ethnicity or skin color—as an imperfect indicator of productivity—is a clear example. But discrimination can also be based on preferences. Figure 3.11 shows that the odds of being unemployed or self-employed are higher for people with darker skin compared to those with lighter skin, even after comparing people with equal educational attainment, reflecting a clear racial bias in hiring decisions.

Figure 3.11 Gaps in employment outcomes by skin color

A. Unemployment

B. Self-employed

Several studies have confirmed the existence of a significant component of labor discrimination in the region. On the one hand, some research has shown that an important part of the wage gap cannot be conclusively explained by obvious characteristics associated with worker productivity (Arcand and D’Hombres, 2004; Card et al., 2021). On the other hand, studies using the technique of sending fictitious resumes to real job offers, where the ethnicity or race of the candidate is randomly modified, have shown a clear bias in hiring, against Afro-descendant and indigenous candidates (Arceo-Gómez and Campos-Vázquez, 2014; Galarza and Yamada, 2014).

Actions to reduce racial-ethnic gaps in labor markets can be grouped into three broad areas. First, reform selection processes to ensure that ethnicity and race are not relevant factors; this would entail eliminating photos and names of candidates in the early stages of candidate selection. Second, implement affirmative action policies, such as minimum employment quotas for disadvantaged ethnic groups in public competitions adopted in Brazil and Uruguay (ECLAC and UNFPA, 2021). Although the evidence on these policies is limited, it suggests that they are effective in increasing the employment of disadvantaged groups without affecting productivity (Holzer and Neumark, 2000). Finally, these policies should be complemented by broader measures that address education and culture, key areas for combating structural discrimination.

Strengthening women’s economic autonomy

Women face specific barriers that limit their social inclusion, especially in the labor market. These inequalities affect more, as is to be expected, those located in disadvantaged contexts. They tend to manifest themselves in various aspects, such as the gap in labor participation and wages, occupational segregation and lower presence in quality formal jobs (figure 3.12.A). In addition, as they tend to bear disproportionate responsibilities for care and unpaid work, their availability to participate fully in the labor market is restricted (figure 3.12.B). Although the allocation of time between paid and unpaid work could be justified by comparative advantages, the evidence tends to reject this idea2. Institutional factors such as limited childcare overage or parental leave policies, as well as social norms, play a preponderant role (Berniell et al., 2023; Kleven et al., 2019, 2024; Olivetti and Paserman, 2015). This situation not only negatively affects women’s economic autonomy, but also limits the efficient allocation of talent in economies, contributing to lower productivity.

Figure 3.12 Gender gaps: labor market and household chores

A. Labor market gaps by educational level (percentage difference). Average for 18 Latin American and Caribbean countries, circa 2022

B. Hours per week spent on housework and unpaid care, by income quintile. Average for several Latin American countries

The gender gap in labor participation declined considerably during the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s. During that period, it went from 40 to 30 percentage points in 2010, but has stagnated since then. This phenomenon contrasts with the remarkable educational progress achieved by women in recent decades, even surpassing men in years of schooling (Marchionni et al., 2019). Recent studies highlight motherhood as the central factor in explaining the gender gaps (Kleven et al., 2019), as this factor is responsible for almost half of the income inequality between men and women (Marchionni and Pedrazzi, 2023). This result is unequivocal in several countries in the region, where it is observed that women’s labor trajectories are significantly affected after the birth of the first child and do not recover, even after several years3. In contrast, the birth of children has practically no impact on men’s labor trajectories. Figure 3.13.A illustrates this phenomenon in the case of Chile. In the region, not only is there a marked decrease in the labor participation of women after childbearing, similar to what occurs in developed countries, but also the quality of their employment is considerably altered, increasing labor informality (figure 3.13.B). This may be due to the need for jobs with flexibility, which the formal sector typically lacks (Berniell et al., 2021).

Figure 3.13 Labor trajectories of mothers and fathers after birth of first child in Chile (percentage changes with respect to the year prior to the birth)

A. Impact on labor participation

B. Impact on informal employment (conditional to work)

Closing gender gaps in the labor market requires actions that help families reduce the time and money constraints associated with child and dependent care. As mentioned, the expansion of childcare services is fundamental, especially to improve the situation of the most vulnerable women (Berlinski et al., 2011; Berlinski, S. and Galiani, S., 2007; Morrissey, 2017). A complementary measure would be to extend the school day in basic education.

The policy package should also focus on the revision of labor and social security legislation with the purpose of extending parental leaves with a gender-neutral approach, avoiding discrimination against women (Arreaza et al., 2023). Parental leaves are mainly focused on maternity, while paternity leaves are very short. This revision should promote co-responsibility between fathers and mothers. It should also ensure that there is no discrimination in the formal employment of women, avoiding cost gaps between the hiring of men and women.

Policies that favor the presence of women in better-paid and higher-quality occupations are also required. These should include curricular and pedagogical reforms throughout the educational cycle that are more gender-neutral and that explicitly encourage women to invest more in training aligned with future labor demands. They also include affirmative action policies that promote female participation in leadership roles.

Finally, it is essential to implement policies that promote changes in gender social norms, moving, for example, towards greater co-responsibility in caregiving tasks. This includes awareness campaigns on gender equality, educational programs for an equitable sharing of household chores, and the promotion of male role models in caregiving.

The most extreme manifestation of the adversities faced by women is, without a doubt, gender-based violence. According to data from the World Health Organization, one in three women has suffered some form of physical or sexual violence by a partner or another person. Gender-based violence has enormous repercussions on women’s physical and mental health and economic conditions. It is a multidimensional public problem: it affects public health, safety and human rights. It is crucial to continue strengthening comprehensive public policies to prevent and combat gender-based violence, supported by studies and technological tools that improve data collection and statistics (Aguirre et al., 2022).

Although not explicitly aimed at reducing gender gaps, income transfer policies, such as conditional or non-contributory pensions, have collaborated in that direction by improving women’s autonomy in managing household resources and their power to negotiate decisions about their lives and those of their children (Alemann et al., 2016; Berniell et al., 2020). They have also helped delay early marriage, reduce beneficiaries’ fertility, increase contraceptive use, and reduce the likelihood of women experiencing physical violence by their partners (Bastagli et al., 2016).

Promoting financial inclusion and access to critical assets

Latin America and the Caribbean is characterized by a high concentration of wealth, even greater than that of income. The poorest 50 % of the population accumulates only 1 % of wealth, while the richest 10 % concentrates 78 % (WID, 2022). Evidence indicates that reaching certain minimum thresholds of wealth is even necessary to overcome poverty traps (Balboni et al., 2022). In this context, access to critical assets such as housing and other productive assets, together with financial inclusion, are fundamental to closing these poverty and inequality gaps.

For a large part of the population, the most relevant asset is housing (De la Mata et al., 2022). However, tenure gaps between the rich and poor sectors have continued to grow in recent decades. While access to housing is relatively high, there is a marked socioeconomic gradient in quality, particularly in terms of access to basic services such as drinking water and sanitation, as well as formal tenure. Housing in informal settlements and without access to public services remain the reality for many vulnerable sectors (Daude et al., 2017). On the other hand, the tenure of productive assets such as commercial premises or land also follows a socioeconomic pattern, with significantly limited access for the poorest sectors. Structural barriers faced by these groups include both lack of sufficient income and lack of access to adequate financial instruments and knowledge that could facilitate the acquisition and improvement of these assets.

In this regard, subsidies and transfers play a fundamental role in guaranteeing access to housing for lower-income households. Some studies have shown that cash subsidies for housing purchase, instead of State construction, can be more efficient and transparent, as they reduce costs and allow families to choose the location of their preference (Bouillon, 2012).

In addition, land titling programs have proven to be effective in improving housing investment and household health. This process allows households to formalize their properties, facilitating access to credit and promoting investment in housing improvements (Galiani and Schargrodsky, 2010). However, it is crucial that these programs also focus on maintaining formality in future transactions, preventing high registration costs from perpetuating informality in successive property transfers.

On the other hand, financial inclusion policies should be diverse, ranging from training in economic issues to improving access to banking services. The inhabitants of the region are characterized, for the most part, as having little financial literacy. This trend is directly proportional to socioeconomic level (Azar et al., 2018), as shown by the results of CAF’s financial capability surveys (figure 3.14), in which, in addition, low financial literacy is evident for women. Financial inclusion policies integrated in the school education system and in conditional transfer programs can be a powerful tool to improve financial management in vulnerable groups. Many of the conditional transfer programs already include financial education components (García et al., 2013). In addition, the participation of State financial institutions is also critical, as the private sector can provide them, but in a way that is not ideal due to the externalities they generate in credit markets (Laajaj and Yang, 2018).

Training programs in this field not only improve knowledge, but also the financial behavior of the beneficiaries (Kaiser et al., 2022). ). And when properly implemented, they have significant economic effects, especially in disadvantaged sectors (figure 3.14). In Peru, for example, a financial education pilot in high school not only had considerable impacts on the financial literacy of young people, but also had effects on their credit behavior three years later, when they were already graduated from high school (Frisancho, 2023a). A spillover effect from children to parents was also evident (Frisancho, 2023b).

Figure 3.14 Percentage of people with good financial knowledge according to gender and educational level

In addition to financial training, it is essential to improve access to banking services for the most vulnerable. This includes developing regulatory policies that encourage the growth of microfinance and fintechs, improving credit bureaus and promoting the digitalization of these services (Mejía and Azar, 2021). In recent decades, the microfinance industry has made significant progress in countries such as Bolivia and Peru, facilitating access for sectors traditionally excluded from the formal financial system. The use of new technologies represents an opportunity for financial inclusion and reinforces the need to consolidate policies to close access gaps, with greater internet coverage and digital literacy for vulnerable groups.