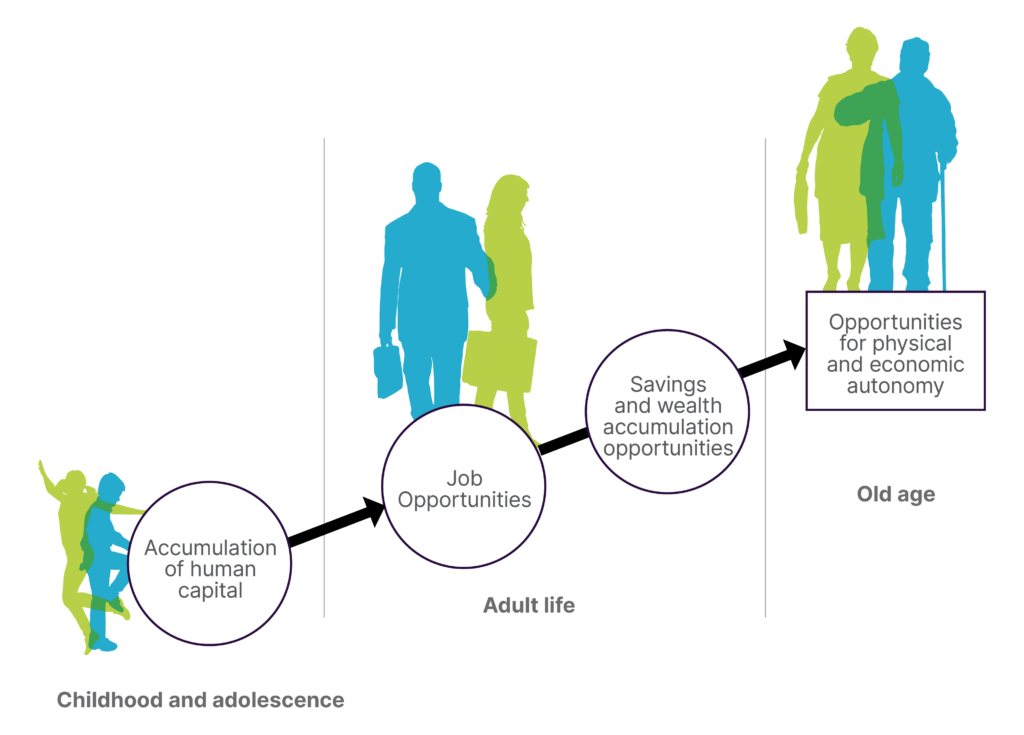

Life cycle and key dimensions of social inclusion

Social inclusion is a complex process that depends on several factors throughout the life cycle. These factors evolve sequentially and interdependently, giving rise to an itinerary of opportunities and challenges. Diagram 3.1 illustrates a simple scheme for thinking about social inclusion policies, where the life course is divided into three stages: the first covers the first two decades, where human capital formation is crucial; the second covers adulthood, with job opportunities and wealth accumulation; and the third, old age, where income, health and care protection must be guaranteed.

The adequate development of human capital during the first two decades of life is crucial for full inclusion. This consists of a broad set of fundamental skills, from physical and mental health to cognitive and socioemotional skills, which later enable the acquisition of specialized knowledge. Skills are not innate or fixed. Growing evidence shows that skills accumulate throughout life. This same evidence also indicates that some stages of life are more important than others. The most crucial moments begin during gestation and culminate after adolescence. This is when the greatest changes occur at the biological and social levels, and it is also when the foundations for all subsequent development are laid. In this process, investments by families, educational and health institutions, and the physical and social environment will be crucial to establishing solid skills.

These skills will enable access to quality job opportunities in adulthood, away from informality and low-productivity self-employment. Access to formal jobs in the region is currently synonymous with better social protection conditions, higher salaries and better opportunities for professional development. Public policies focused on the most vulnerable groups to facilitate their transition to formality, as well as to cushion negative shocks in the labor market, are critical in an agenda that seeks to break down the deepest barriers behind social exclusion.

Employment opportunities also determine the capacity to save and accumulate wealth, in which access to credit and adequate financial knowledge play a fundamental role. People with access to these opportunities can improve their quality of life and ensure a more stable future. Equitable access to financial resources is fundamental to reducing vulnerability and promoting investment in education, health and housing.

Old age presents challenges in terms of inclusion and it is essential to ensure protection in terms of income, health and care. Equitable opportunities throughout the life course are particularly relevant at this stage, since many people depend on the resources accumulated in previous stages to face this phase. In turn, the insurance mechanisms provided by social protection systems are key to ensuring a life course in old age that is not interrupted by health shocks, reduction of income during the period of retirement from the labor market and other types of vulnerabilities.

Diagram 3.1 Key opportunities throughout the life cycle to foster social inclusion

The virtuous circle between human capital formation, employment, savings, asset accumulation and protection in old age is not limited to a single generation: the achievements of an individual have an impact on the opportunities that their children will have. This view highlights the need for comprehensive policies that recognize their potential intergenerational impacts and provides additional motivation to encourage redistributive policies. For example, monetary transfers to adults or older adults can have an impact on children, to the extent that these resources are used in the formation of their human capital.

The reason why a large part of the population does not accumulate human capital, does not have access to quality jobs, does not save, and does not have protection in old age is that there are a significant number of barriers. Identifying them is critical when designing and targeting public policies for inclusion. And among them is a central one, faced by most families in the region: the financial constraint of making investments with a positive return. Poor families do not have sufficient resources to ensure proper nutrition, cover health, education and care expenses, or have access to adequate housing in environments that favor the development of their children. Educational and residential decisions, made under limited financial conditions, also determine to a large extent the quality of education and of the environment, both physical and social, in which children and young people develop.

These challenges worsen when basic public services are deficient or inaccessible. In turn, they are accentuated by limited access to credit, which is not available as a tool to undertake larger investments, such as housing, or to cope with negative income shocks. This vulnerability is intensified by the health, economic, technological or environmental risks that arise throughout life, which have an unequal impact, depending on the socioeconomic level.

The ability of families to protect themselves through insurance mechanisms, both private and social, is key to guaranteeing stable trajectories, mitigating negative events and avoiding the loss of savings or assets. The poorest in the region face limited insurance, as the type and quality of coverage provided by social security systems generally depend on the labor market status of workers. The lack of insurance is critical for the formation of human capital, especially in key stages such as the prenatal period and the first years of life, where the lack of investment can have irreversible effects. In addition, the most vulnerable households are more exposed to all kinds of unforeseen events that affect their income, jobs and wealth accumulation.

Social insurance regulations come from 19th century Europe, from a model where social protection is associated to the relationship between the company and the worker […] The States of the region give asymmetric treatment to the same person depending on the labor contract he/she has […] If we want social inclusion, we have to rethink in depth how we structure social protection in the region. We must stop going down the same path of simply adding more and more programs and more and more spending without having any logic and any coherence in what is being done.

Based on an interview with Santiago Levy

There is another broad set of non-financial barriers to inclusion that often act through more subtle mechanisms. These are equally important and include aspects such as lack of knowledge and information, social norms, discrimination and space constraints, among others. Overcoming them requires policies that strengthen access to information to improve decision making at specific stages of the life course (such as information to strengthen parenting or on wage returns by college degree to improve student decision making), or broader policies that transform key cultural norms to reduce gender and racial-ethnic gaps. Spatial barriers, meanwhile, require context-specific policies, including bringing essential services closer to vulnerable households or improving mobility to facilitate access to opportunities.