The triple challenge for the development of Latin America and the Caribbean

The multidimensionality of development

The concept of development has evolved over time. From a restrictive vision that emphasized per capita income levels, it has evolved to a broader one, which transcends income-based measures and also includes distributive and environmental sustainability aspects.

Clearly, the process of development implies a significant improvement in people’s quality of life, which undoubtedly depends on income. Hence, per capita income growth is an essential dimension of development. In fact, this dimension has been the focus of the global vision of development since World War II.

However, since the 1970s, concrete efforts have been made to adopt a broad perspective on well-being and measurements of progress in development. The need to include poverty as a first element was evident. One example was the basic needs approach, whose institutional origins date back to the 1976 World Employment Conference of the International Labor Organization (Reinert, 2023).

Under this vision, in the early 1980s, ECLAC introduced the measurement of unsatisfied basic needs (UBN) as a tool for social diagnosis and support for the implementation of social programs. This methodology chose a series of census indicators that made it possible to determine whether or not households were meeting some of their main needs. Due to data availability, the needs considered were usually limited to four categories: (i) access to housing that ensured a minimum standard of habitability, (ii) access to basic services that ensured an adequate level of sanitation, (iii) access to basic education and (iv) economic capacity to reach minimum levels of consumption (Feres and Mancero, 2001).

Progress towards a multidimensional vision of development continued over the next two decades with a series of reflections and conferences, highlighting aspects such as gender, children, food, health and, with increasing importance, the preservation of nature and the environment.

These efforts and reflections were the basis for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), derived from the Millennium Declaration, proclaimed by more than 150 world leaders at the Millennium Summit held in September 2000. The eight goals highlighted in the declaration for 2015 were: (1) eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, (2) achieve universal primary education, (3) promote gender equality and empower women, (4) reduce child mortality, (5) improve maternal health, (6) combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, (7) ensure environmental sustainability, and (8) develop a global partnership for development. Each goal entailed specific targets; for example, one of the specific targets for goal 1 was to reduce by half, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people with an income of less than one dollar a day.

In September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 70/1, entitled «Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,» which stated: The new agenda builds on the Millennium Development Goals […] In its scope, however, the framework we are announcing today goes far beyond the MDGs. Alongside continuing development priorities such as poverty eradication, health, education, and food security and nutrition, it sets out a wide range of economic, social and environmental objectives (United Nations, 2015b).

With this resolution, the MDGs were updated to 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with 169 associated targets. Among the additions, in relation to the MDGs, are the explicit incorporation of the reduction of inequality (SDG 10) and gender equality (SDG 5), as well as specific environmental targets related to ocean conservation (SDG 14), forest sustainability and biodiversity protection (SDG 15), and climate change and its effects (SDG 13). As expected, the SDGs also include targets related to economic growth, quality employment and innovation (SDGs 8 and 9).

Diagram 1.1 SDGs

Diagnosis of the region: glass half full, glass half empty

The degree of compliance with the targets associated with the SDGs offers a panoramic view of the region’s development. ECLAC (2024) provides an analysis with data as of February 2024, classifying the targets for each of the 17 goals1 in four possible categories: (1) the trend is far from the target, (2) the trend is correct but progress is too slow to achieve it, (3) the target has been achieved or is likely to be achieved, and (4) there is insufficient data. The results are presented both for the region as a whole and for three sub-regions: South America, Central America, and Mexico and the Caribbean (see figure 1.1).

For the region, only 22 % of the targets that have been projected show compliance horizons to 2030. Around 46 % of the targets are still on track, but would need to accelerate the pace of progress to reach the established thresholds. Finally, 32 % of the targets are regressing with respect to the starting point in 2015. It is worth noting that even within the various goals, in general there are targets that are on track to be met and others that show backsliding. When contrasting between subregions, South America shows some slight advantages, but a similar picture.

Figure 1.1 SDG targets by degree of achievement

Measuring the development of nations on an extensive set of indicators, as is the case with the SDGs, is valuable for bringing to light the different key aspects of development omitted by GDP per capita. However, the sheer complexity of the system can itself be a challenge in guiding public policy within a country.2

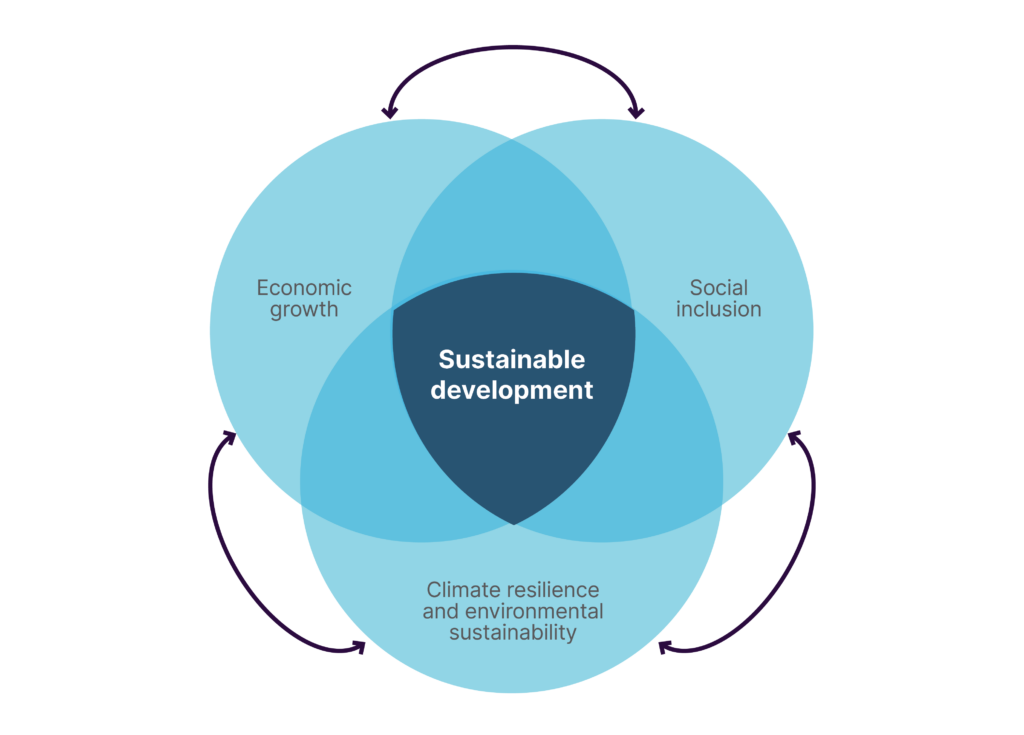

A common way of approaching the multidimensionality of development is through three areas of analysis. The first is economic growth, to close the huge and persistent per capita income gap with the developed world. The second is inclusion, to ensure that economic growth reaches everyone and reduces poverty and the strong inequality in the region. The third is sustainability, pursuing three objectives: adapting to and improving resilience to climate change, contributing to the global reduction of emissions, and preserving natural capital.

Diagram 1.2 The three areas of sustainable development

However, these are not isolated areas, but interact with each other. This implies that there are risks of underdevelopment traps with low levels of per capita GDP, environmental degradation and high levels of poverty and inequality. However, these interactions also enable the possibility of virtuous circles, where progress in the three areas of sustainable development is mutually reinforcing (see Box 1.1).

What we have observed in developed countries, in general, is that, in order for the process of growth and development to be sustained and inclusive, the population employed in low productivity sectors must move, by the force of demand and the demand for goods and services, to the higher productivity sectors.

Based on an interview with Nora Lustig

While there are tensions and there may be vicious circles between the different dimensions that are important for economic and social development […], there are also complementarities. And I believe that good public policy needs to exploit these complementarities so that progress in favor of one dimension, for example, growth, is compatible with and helps progress in another dimension of economic and social development, such as environmental sustainability or social equity.

Based on an interview with Santiago Levy

Box 1.1 Interrelationships between areas of sustainable development

Growth, inequality and poverty

There is evidence from the developed world that innovation and technological change can increase the wage gap between the most and least educated and, with it, wage inequality (Acemoglu, 2002). Informality, on the other hand, explains the low productivity of the economy and also wage inequality. On the other hand, social inclusion favors economic growth by promoting a better allocation of talents (Hsieh et al., 2019).

Connection between growth and sustainability

Climate change affects growth and productivity. Extreme weather events, whose frequency and intensity are increasing due to global warming, cause loss of human lives and damage to infrastructure, compromise agricultural production and impact the accumulation of human capital. Productivity gains, including those in the agricultural sector, can simultaneously favor economic growth and environmental protection, since they imply lower energy use and natural capital depreciation per unit of output. However, gains in the efficiency with which a natural resource can be exploited can also result in greater demand for the resource, aggravating the pressure on ecosystems. Finally, the increase in household income is accompanied by an increase in the consumption of most goods, the production and disposal of which generate adverse consequences for the environmental balance.

Connection, inclusion and sustainability

Extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods, affect the poorest more strongly, becoming a factor that amplifies inequality. On the one hand, lower-income households are more exposed to these events than the rest of the population, partly because they live in riskier areas (Winsemius et al., 2018). On the other, they are more vulnerable; that is, in the case of suffering an event, it is more likely to have severe and persistent negative effects. Also, poverty and inequality impose certain restrictions on the adoption of clean or energy-efficient technologies in households, partly due to limitations in financing these measures.

To gain a more detailed perspective on the dynamics of regional development, we will review a reduced set of key indicators in each of the three areas of sustainable development. For each area we will highlight the most salient fact:

Fact # 1: The region has experienced per capita GDP growth, although this has been insufficient to significantly reduce the gap with the developed world.

Between 2010 and 2019, real GDP per capita in Latin America was more than 4.4 times the average for the period 1950-1959. For the Caribbean, this value was 2.4 times higher (figure 1.2, see left panel). However, this growth has been insufficient to close the per capita GDP gap with the developed world, e.g., the United States, which has remained practically unchanged and below 30 % in recent decades (see figure 1.2, right panel).

Figure 1.2 Evolution of GDP per capita

A. Average GDP per capita relative to the average of the 1950s

B. Average GDP per capita relative to the United States

Fact # 2: In the last two decades there has been a reduction in inequality and poverty, but we are still one of the most unequal regions and maintain very high levels of poverty.

Total poverty fell significantly in the first decade of the 21st century. Then, this fall slowed and reversed slightly from the middle of the second decade of the century, with a rebound associated with Covid-19. Despite this improvement, according to the most recent data, almost 30 % of the population in Latin American and the Caribbean live in poverty and more than 10 % in extreme poverty. In rural areas, the incidence of poverty exceeds 40 % and extreme poverty almost 20 %. These levels are well above those recorded in developed regions (figure 1.3). The Gini index, a classic measure of inequality, also shows a favorable trend so far this century; however, according to this indicator, the region is among the most unequal in the world in terms of income distribution.

Figure 1.3 Poverty and inequality dimension

A. Evolution of poverty rates in Latin America, by country and region

B. Evolution of the Gini index of income distribution

Latin America is a region that has excess poverty. [….] and one of the essential sources of why there is excess poverty is precisely because it is one of the most unequal regions in the world. Why are we in such an unequal world in Latin America? […] Because the type of development that is taking place does not generate enough jobs to offer opportunities to people who come with low levels of education or training.

Based on an interview with Nora Lustig

The flip side of this reduction in poverty experienced by the region in recent decades is a significant growth of the middle classes in Latin America and the Caribbean. According to estimates, the middle class went from representing about 20 % of households at the beginning of the century to 38 % in 20193 (World Bank, 2021).

Middle-class growth represents an opportunity to boost the region’s economic and social development. However, existing challenges need to be addressed to consolidate this progress. A particularly relevant challenge is that a large part of the region’s middle class is in a vulnerable situation, susceptible to falling into poverty in the face of economic shocks. For example, Stampini et al. (2016) find that in the region 14 % of middle-class people fall into poverty at least once in a 10-year period.

Fact # 3: In the region, per capita GHG emissions are lower than in other regions such as North America. Nevertheless, there is high exposure to the consequences of climate change. In addition, there is an accelerated deterioration of natural capital.

According to the most recent estimate, per capita GHG emissions in Latin America and the Caribbean are less than half those of North America, and also lower than those of other regions such as East Asia and the Middle East (figure 1.4). On the other hand, the region has been responsible for 11 % of anthropogenic GHG emissions since 1850.

Figure 1.4 GHG Emissions by Population and GDP

A. Emissions per capita

B. Emissions per unit of GDP

In terms of emissions composition, Latin America is characterized by the importance of its non-energy emissions. Globally, almost 80 % of GHG emissions come from fossil energy consumption and industrial processes (FECIP), while just over 20 % come from the AFOLU sector (agriculture, forestry and other land uses). In contrast, in Latin America, about 55 % of emissions come from this sector, a much more significant amount than the 14 % in the Caribbean or 8 % in OECD countries (see chapter 4).

However, the importance of this component has been falling in the region. During the periods 2000-2009 and 2010-2019, total emissions in Latin America contracted significantly, even turning negative in the last decade (-3.8 %) due to a sharp fall in the AFOLU component (-10.3 %), which offset the growth of the FECIP component (5.2 %). Something similar occurred in the Caribbean region, where, in the last decade, there was even a reduction in both AFOLU emissions (-15.6 %) and FECIP (-2.5 %), resulting in a fall in total emissions (-4.4 %) (see figure 4.5).

Figure 1.5 Growth of GHG emissions

Aside from its responsibility for emissions, it is a fact that the region is suffering considerably from the consequences of climate change. Since 1980, the occurrence of extreme weather events has increased almost twofold (see chapter 4). There has also been a significant increase in the number of people affected. These events tend to hit the most vulnerable families hardest, as well as certain sectors such as agriculture and tourism.

Sea level rise is causing erosion; it is damaging coastal regions. Guyana, for example, has saltwater intrusion damaging their agricultural communities along the coast, and so on and so forth. And then, of course, there are more intense hurricanes, much more difficult weather patterns, rain when it’s supposed to be dry and drought when it’s supposed to be rainy. These are challenges that the Caribbean must overcome if it is to be sustainable.

Based on an interview with Colm Imbert

The recent history of the region also points to a significant deterioration of natural capital. Between 1990 and 2014, natural capital per capita contracted in the region by about 40 % (Sanguinetti et al., 2014). Moreover, the region has been consuming its natural capital faster than the global average. Thus, according to the Inclusive Wealth2023 report of the United Nations environmental program (2023), by 1990, the region had more than 21 % of the value of natural capital, but, by 2019, the figure had fallen to 13.77 %. Likewise, the Living Planet Index shows an alarming loss of biodiversity over the last 50 years (see chapter 4). Sustainable use of our natural capital will be key to promoting sustainable development.

Undoubtedly, we have to look for ways to generate income from our own biodiversity, protecting it. We must generate resources and ensure that they reach, above all, the most vulnerable sectors of the population.

Based on an interview with Mauricio Cárdenas